In automated industrial piping systems, the valve is the “switch and regulator” of media flow. Its control accuracy directly impacts production efficiency, safety, environmental compliance, and energy costs. The Valve Positioner—the valve’s core accessory—is equivalent to installing a “precise control brain” onto the valve, solving the critical mismatch between the actuator and the control signal. This makes the positioner an indispensable component in modern automation.

This article, written from an industrial application perspective, dissects the core function, working principle, and typical scenarios for valve positioners to help professionals fully grasp their technical value.

Table of Contents

ToggleI. Why a Valve Positioner is Essential: The Pain Points of Traditional Control

In industrial settings, valve actuators (such as pneumatic diaphragm or electric actuators) directly drive the valve core. However, relying solely on the controller’s output signal (e.g., 4 – 20mA current) often fails to achieve precise control due to three major pain points:

The Standard Control Logic: 4 – 20 mA Linear Correspondence

The core logic of automation systems is a linear relationship between the input signal (current) and the valve opening (stroke), unless specifically configured otherwise:

| Current Signal (Input) | Valve Opening (Stroke) | Flow Status |

| 4mA | 0% Open (Fully Closed) | Complete media shut-off. |

| 8mA | 25% Open | Quarter flow regulation (for low flow adjustment). |

| 12mA | 50% Open (Mid-position) | Medium flow rate. |

| 16mA | 75% Open | Three-quarters flow regulation (for high flow adjustment). |

| 20mA | 100% Open (Fully Open) | Maximum media flow. |

Fault Detection Tip: A signal below 4 mA or above 20mA is usually interpreted as a line fault (e.g., open circuit, short circuit), preventing misoperation.

Specialized Non-Linear Correspondence (Configured via Positioner)

For specific processes requiring non-linear flow control, the positioner allows custom mapping:

Equal Percentage Mapping: Signal growth corresponds to exponential flow increase (e.g., 4 – 12 mA might map to 0 – 50% opening, while 12 – 20mA maps to 50 -100%). Ideal for reactor feeds requiring precise micro-adjustment at low openings.

Quick Opening Mapping: Small signal changes achieve large opening changes (e.g., 4 – 8mA achieves 0 – 60% opening). Ideal for fast shut-off or high-capacity transfer lines.

1. Large Signal-to-Actuation Deviation

The controller’s electrical signal cannot directly meet the power needs of the actuator (e.g., pneumatic actuators need air pressure). Furthermore, signal transmission is prone to interference, leading to a mismatch between the desired opening and the actual valve core position.

2. Control Accuracy is Compromised by External Interference

Factors like pipe pressure fluctuations, changes in media viscosity, or actuator wear/aging cause variations in the actuator’s output force. This results in “sticking” or “drifting” of the valve core, making it impossible to hold a stable set point.

3. Lack of Feedback and Diagnostics

In traditional control, the controller cannot obtain real-time feedback on the valve core’s actual position. If a valve failure occurs (e.g., sticking, leakage), the system cannot respond immediately, potentially leading to production accidents.

The valve positioner precisely solves these issues through a “signal conversion, amplification, and feedback” closed-loop logic, upgrading valve control from “crude regulation” to “precise controllability.”

II. Core Functions of the Valve Positioner

The positioner’s primary value lies in the “precise matching of the control signal to the actuator’s movement.” Its function can be summarized in four core areas:

1. Signal Conversion and Amplification

The positioner converts the standard electrical (4 – 20mA) or pneumatic (0.02- 0.1MPa) signal from the controller into the power signal required by the actuator (e.g., 0.02- 0.1MPa air pressure for a pneumatic actuator). It also amplifies the signal power, ensuring the actuator has sufficient force to drive large valve cores, especially crucial for large-diameter, high-pressure service.

2. Precise Valve Core Positioning

Using closed-loop feedback, the positioner continuously monitors the valve core’s actual position (via a position sensor) and compares it against the controller’s set point. If a deviation exists, the positioner automatically adjusts its output until the valve opening matches the set point, achieving a control accuracy typically around pm 0.5, far exceeding traditional methods.

3. Counteracting External Interference and Stabilizing Control

When faced with disturbances like pipeline pressure fluctuations, changes in media resistance, or actuator wear, the positioner’s rapid feedback mechanism adjusts the output power to counteract the effect of the interference.

Example: If a pneumatic diaphragm loses output force due to aging, the positioner automatically increases the output air pressure to ensure the valve core firmly maintains the set position.

4. Status Feedback and Fault Diagnostics

Built-in sensors allow the positioner to collect real-time data on valve core position and actuator pressure, providing the controller with a live “set point vs. actual value” monitoring capability. Furthermore, smart positioners include diagnostics to detect issues like valve sticking, actuator leakage, and friction changes, issuing alerts for timely maintenance.

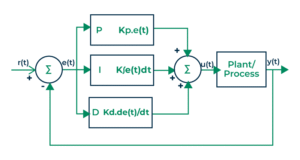

III. Working Principle Simplified: The Three-Step Closed-Loop Logic

The operation of a valve positioner is essentially closed-loop feedback control. Taking the widely used pneumatic positioner as an example, the workflow is simplified into three steps:

Signal Reception and Conversion: The 4 – 20 mA electrical signal from the controller is converted by internal circuitry into an electromagnetic force or electrical signal that drives an internal flapper or nozzle.

Power Signal Amplification: The converted signal is amplified, controlling a pneumatic amplifier (booster) to output the corresponding air pressure (e.g., 4 – 20mA corresponds to 0.02 – 0.1 MPa pressure) to drive the actuator’s diaphragm or piston.

Feedback and Error Correction: A position sensor (e.g., feedback arm, Hall sensor) collects the valve core’s actual opening signal and feeds it back to the positioner’s comparison circuit. If a deviation exists, the comparison circuit adjusts the output signal until the error is eliminated, achieving precise positioning.

⚙️ Field Operation Guide: Signal-to-Stroke Calibration (Must-Know)

The accuracy of the signal-to-stroke relationship must be guaranteed through calibration. A simplified procedure for a pneumatic positioner:

Preparation: Connect all components. Manually set the valve to the fully closed position.

Zero Calibration (4mA): Output a 4mA signal from the controller. Adjust the positioner’s “Zero Knob” until the valve is completely closed (0% stroke) with no leakage.

Span Calibration (20mA): Output a 20mA signal. Adjust the positioner’s “Span Knob” until the valve is fully open (100\% stroke), verifying the actual travel matches the rated travel.

Mid-Point Verification (12mA): Output a 12mA signal. Check if the valve opening is exactly 50\%. If the deviation exceeds the industrial standard (≤± 1%), Zero and Span until the linearity is acceptable (≤± 0.5%).

Fault Simulation Test: Intentionally lower the signal to 3mA (below standard) to ensure the positioner triggers a fault warning, verifying the diagnostic function.

IV. Critical Application Scenarios: Where Positioners are Mandatory

Valve positioners are not required everywhere, but they are essential components in automated systems that demand high control accuracy and stability.

Process Control Industries: In Chemical, Petrochemical, and Pharmaceutical plants (e.g., reactor feed control, temperature/pressure regulation). Positioners ensure precise flow and pressure control, guaranteeing stable reaction conditions.

Energy and Power Systems: In steam lines and feedwater regulation systems in thermal/nuclear power plants. In high-pressure, high-temperature service, positioners compensate for pressure fluctuations, preventing energy waste and ensuring stable operation.

Water Treatment: In dosing systems and flow regulation lines (e.g., water/sewage treatment plants). Positioners ensure precise chemical dosage and flow consistency, enhancing treatment effectiveness.

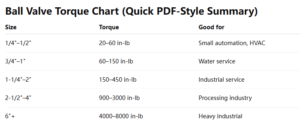

Large-Bore / High-Pressure Valves: For valves DN ≥ 300mm or PN ≥ 4.0 MPa. The actuator requires high driving force; the positioner’s signal amplification satisfies this power demand while maintaining precise positioning.

Summary: The Invaluable Role of the Positioner

The valve positioner, though a relatively small component, acts as the “key supporting actor” that directly determines the accuracy and stability of industrial automation control.

Its core function—through signal conversion, precise positioning, interference cancellation, and status feedback—upgrades the valve from “passive executor” to “active, precise responder.” It is an indispensable heart of any automated piping system.

Final Consideration: In practice, selection must be carefully matched to the actuator type (pneumatic/electric), process parameters (pressure, temperature, medium), and control requirements (choosing pneumatic, electric, or smart digital positioners).