Imagine a process where tiny, microscopic bubbles act like high-speed jackhammers, literally eating away at your solid stainless steel valve trim. This is Cavitation. It is one of the most destructive forces in fluid mechanics, capable of turning a high-performance control valve into scrap metal in a matter of weeks.

If your valve sounds like it is “shaking marbles” or “pumping gravel,” you have a cavitation problem. This guide explains the physics of why it happens and how to engineer your way out of it.

Table of Contents

Toggle1. The Physics: Why Bubbles “Eat” Metal

Cavitation is a two-stage process that happens inside a control valve due to pressure changes:

Phase 1 (Vaporization): As fluid passes through the narrow orifice of the valve (the vena contracta), its velocity increases and its pressure drops below the fluid’s vapor pressure. Tiny vapor bubbles form.

Phase 2 (The Implosion): As the fluid moves downstream, the pressure recovers. These bubbles suddenly collapse (implode).

The Damage: The implosion creates a localized micro-jet and a shockwave (up to 100,000 PSI). If these implosions happen near the metal surface, they blast away small particles of the material, leading to a “cinder-block” or “pitted” appearance.

2. Recognizing the Symptoms

Don’t wait for a leak to diagnose the problem. Watch for these three signs:

The “Gravel” Noise: A distinct rattling sound that sounds like rocks moving through the pipe.

Severe Vibration: High-frequency vibration that can loosen actuators and sensitive instruments.

Erratic Flow Control: As the valve trim is eaten away, the flow characteristic (Cv) changes, making it impossible for your PLC to maintain a steady setpoint.

3. Five Strategies to Stop Cavitation

Strategy A: Multi-Stage Pressure Drop (The Best Solution)

Instead of forcing the pressure to drop all at once, use a Multi-Stage Trim. This design forces the fluid through a series of “steps” or “mazes.” By dropping the pressure gradually, it never falls below the vapor pressure, preventing bubbles from forming in the first place.

Strategy B: Labyrinth or Drilled-Hole Cages

Using a cage with hundreds of tiny drilled holes (Multi-path) breaks the flow into small “jets.” These jets collide with each other in the center of the valve, away from the metal walls. Even if bubbles implode, they do so in the fluid stream, not on the metal surfaces.

Strategy C: Hardened Trim Materials

If the cavitation is mild and cannot be avoided, upgrade the trim to hardened materials like Stellite, Tungsten Carbide, or 440C Stainless Steel. This won’t stop the physics, but it will extend the valve’s life significantly.

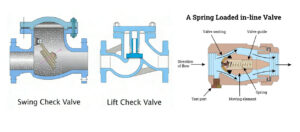

Strategy D: Change the Valve Type

Standard butterfly and ball valves are prone to cavitation when throttled. Moving to a Globe-style control valve provides a more tortuous path for the fluid, which helps manage pressure recovery more safely.

Strategy E: Increase Downstream Pressure

Sometimes, simply moving the control valve further upstream or installing an orifice plate downstream can increase the back-pressure, preventing the “implosion” phase from occurring inside the valve body.

4. Selection Matrix: Anti-Cavitation Comparison

| Method | Effectiveness | Cost | Best For… |

| Standard Trim | Low | $ | Low-pressure, non-critical water. |

| Hardened Stellite | Moderate | $$ | High-cycle, mild cavitation. |

| Drilled Hole Cage | High | $$$ | High-pressure drop gas or liquid. |

| Multi-Stage Maze | Highest | $$$$ | Severe Service / High $\Delta P$ applications. |

Conclusion: Stop Repairing, Start Engineering

Cavitation is not a maintenance issue; it is a design issue. If you are replacing your valve trim every few months, you are treating the symptom, not the disease. By upgrading to an Anti-Cavitation Multi-Stage Valve, you can eliminate the noise, stop the vibration, and ensure your process stays online for years instead of weeks.