In the world of industrial refrigeration, Ammonia (NH3/R717) is a dual-edged sword. While it is one of the most efficient and environmentally friendly refrigerants available, its toxicity and corrosive nature toward copper and its alloys demand a specialized approach to valve design.

For engineers managing cold storage or food processing plants, the integrity of a refrigerant shut-off valve or isolation valve is the only barrier between a safe operation and a hazardous leak. This guide explores the critical material and sealing technologies that ensure long-term reliability in ammonia systems.

Table of Contents

Toggle1. Material Compatibility: The End of Copper Alloys

The first rule of ammonia refrigeration is the total exclusion of copper, brass, and bronze. Ammonia in the presence of moisture (which is inevitable in most systems) aggressively attacks these materials, leading to rapid stress corrosion cracking.

The Steel Advantage

To ensure safety, industrial ammonia valves must be constructed from:

Low-Temperature Carbon Steel (A350 LF2): Ideal for valve bodies, providing excellent impact strength even at temperatures down to -50°C.

Stainless Steel (304/316): Often used for valve stems and internal components to prevent pitting and ensure smooth operation over decades of service.

2. Advanced Sealing Mechanisms: Beyond the Basics

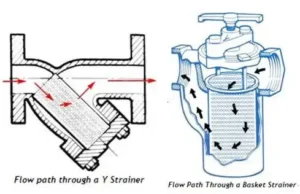

In a typical refrigeration shut-off valve, the sealing system must handle two challenges: preventing internal bypass (seat seal) and preventing external leakage (stem seal).

Elastic Sealing with PTFE and Graphite

Industrial ammonia valves utilize advanced polymers to achieve a bubble-tight seal:

Modified PTFE: Unlike virgin PTFE, modified versions offer lower porosity and higher resistance to “cold flow,” ensuring the seat remains tight even under constant pressure.

Graphite-Reinforced Gaskets: Used for bonnet-to-body sealing, graphite provides exceptional fire safety and maintains a seal during extreme temperature fluctuations.

The Back-Seat Safety Feature

As discussed in our selection guide, the back-seat design is a critical safety redundancy. By allowing the stem to seal against the bonnet in the fully open position, it provides an additional barrier against atmospheric leaks and allows for emergency maintenance of the stem packing without shutting down the entire line.

3. Stem Sealing: The Battle Against “Ice Heave”

In ammonia systems, ice buildup on the valve stem is a common sight. If the valve is not properly designed, this ice can tear the stem packing as the valve is operated, leading to gradual leaks.

Extended Bonnets: High-performance ammonia valves feature an extended neck. This design moves the stem packing away from the cold pipe surface, keeping the packing at a higher temperature to prevent freezing and ensure it remains resilient.

V-Ring Packing Sets: Utilizing spring-loaded V-rings ensures constant contact stress, automatically compensating for the wear and thermal contraction that occurs in high-cycle industrial environments.

4. Preventing “Dry Operation” and Debris Damage

Ammonia is a “dry” refrigerant, meaning it provides very little lubrication for moving valve parts. Furthermore, industrial systems can accumulate welding slag or pipe scale over time.

Hardened Valve Seats: To prevent debris from scarring the sealing surface, many ammonia refrigeration isolation valves utilize hardened steel or ceramic-coated seats.

Self-Cleaning Spools: Designing the internal flow path to create a “scouring” effect helps prevent the buildup of oil sludge or scale in the valve’s critical moving zones.

Conclusion: The Cost of Compromise

In ammonia refrigeration, the cost of a high-quality valve is a fraction of the cost of a single leakage event. By focusing on steel-based metallurgy, extended bonnets, and PTFE-based sealing, engineers can mitigate the risks associated with R717. When searching for refrigerant shut-off valves, always prioritize material certifications and tested pressure ratings over initial cost.