In modern industrial processing, “Vacuum” is not merely the absence of matter; it is a precisely controlled pressure state essential for everything from semiconductor lithography to food preservation. As a critical operating condition, vacuum environments impose unique demands on fluid control hardware. This guide explores the physical nature of vacuum and the engineering logic behind selecting the pumps and valves that manage it.

Table of Contents

Toggle1. Defining the Industrial Vacuum: Standards and Classifications

In industrial terms, a vacuum is any gaseous state below standard atmospheric pressure (101,325 Pa). Since a “perfect vacuum” is theoretically unattainable, industrial applications categorize vacuum levels based on Absolute Pressure:

| Vacuum Level | Pressure Range (Pa) | Typical Applications |

| Rough Vacuum | 10⁵ to 10³ | Vacuum lifting, sewage transport, material conveying. |

| Low/Medium Vacuum | 10³ to 10⁻¹ | Vacuum drying, packaging, thin-film coating. |

| High Vacuum (HV) | 10⁻¹ to10⁻⁶ | Semiconductor fab, vacuum metallurgy, electron beam welding. |

| Ultra-High (UHV) | 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁹ | Nanomaterial synthesis, high-energy physics. |

2. Core Technical Requirements for Vacuum Fluid Equipment

Vacuum conditions reverse the traditional “internal pressure” logic of pump and valve design. The primary engineering focus shifts to leakage prevention and structural integrity under negative pressure.

Hermetic Sealing: External air must be prevented from entering the system. This requires high-precision sealing (Ra ≤ 0.8μm) and advanced technologies like Bellows Seals or V-ring seals.

Structural Rigidity: Equipment housings must withstand the atmospheric crushing force (external pressure vs. internal void) without deformation. High-strength 304/316L stainless steel or titanium alloys are preferred.

Extremely Low Leak Rates: Industrial vacuum valves must typically meet a helium leak rate standard of ≤10⁻⁷· m³.

Media Compatibility: In chemical vacuums, valves must resist corrosive gases (Chlorine, Hydrogen) and volatile solvents while maintaining seal elasticity.

3. Specialized Vacuum Valves: Application Scenarios

Valves serve as the “Gatekeepers” of the vacuum system, providing isolation, regulation, and safety.

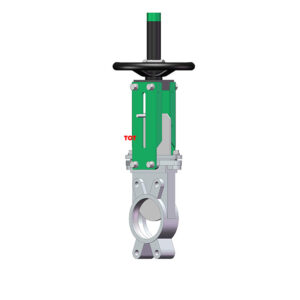

A. Isolation: Vacuum Gate and Butterfly Valves

In semiconductor wafer fabrication and vacuum coating, large-bore gate valves are used to isolate the process chamber from the atmosphere or the pump.

Solution: Opt for Vacuum Gate Valves for high-integrity sealing or Vacuum Butterfly Valves (DN ≥ 200) for rapid cycling and compact footprints.

B. Regulation: Vacuum Control Valves

In chemical vacuum distillation, maintaining a stable pressure (typically 10-100 Pa) is vital for component separation.

Solution: Use Pneumatic Diaphragm Control Valves with smart positioners to achieve a regulation accuracy of ≤± 1%.

C. Safety: Vacuum Relief and Break Valves

To prevent equipment collapse due to excessive negative pressure, or to safely return a system to atmospheric pressure (e.g., in freeze-dryers).

Solution: Vacuum Break Valves with fast-opening structures (< 0.5s) and fluororubber (FKM) seals ensure reliability.

4. Pumps in Vacuum Service: Transport and Suction

Pumps in vacuum applications either create the vacuum (Vacuum Pumps) or must operate efficiently within a negative pressure environment.

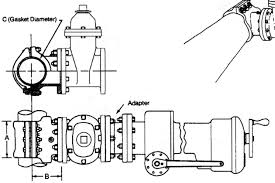

A. Vacuum Priming: Self-Priming Centrifugal Pumps

In municipal drainage where the pump is located above the liquid level, a vacuum must be established in the suction line to draw water up.

Technical Logic: Built-in vacuum chambers allow the pump to evacuate air, achieving a suction lift of 3–8 meters.

B. Vacuum Sewage Transport

Used in green building drainage and environmental projects where gravity-fed lines are impossible.

Technical Logic: The system operates at -0.04 to -0.08 MPa. Pumps must feature Non-clogging Impellers (Open or Semi-open) to handle solids without losing the vacuum seal.

C. High-Purity Transfer: Oil-Free & Magnetic Drive Pumps

In the semiconductor and pharma industries, fluid transfer must happen within a vacuum without any oil contamination.

Solution: A combination of Oil-Free Scroll Vacuum Pumps (to maintain the environment) and Magnetic Drive Centrifugal Pumps (to ensure zero-leakage fluid transfer).

5. Maintenance and Selection Guidelines

Selection Principles:

Match the Vacuum Grade: Do not over-specify (wasting cost) or under-specify (causing system failure). Use HV valves only for HV systems.

Seal Priority: Always prioritize “Bellows Sealing” for hazardous or ultra-pure vacuum media.

Media Phase: If the medium contains steam, ensure valves have Heating Jackets to prevent condensation, which can scale and destroy the sealing faces.

Maintenance Measures:

Seal Inspection: Replace elastomeric seals every 6–12 months. Polish metal seats with grinding paste if scratches are detected.

Monitoring: Install Thermocouple or Ionization Vacuum Gauges at critical nodes to detect rapid pressure rises (indicating a leak).

Oil Maintenance: For oil-sealed pumps, change oil regularly to prevent acidity and particulate buildup.

Conclusion: The Future of Vacuum Fluid Control

As we move toward “Industry 4.0,” vacuum pumps and valves are becoming smarter and greener. The future lies in Intelligent Vacuum Valves with integrated sensors for real-time leak detection and Variable Frequency Vacuum Pumps that reduce energy consumption by up to 30%. Understanding the physics of the void is the key to mastering high-precision industrial production.