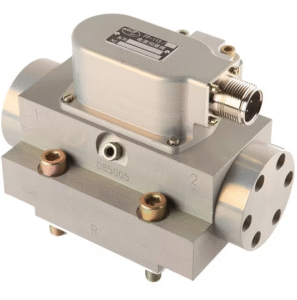

Manual valves are fine for isolation, but in modern industrial plants, efficiency is driven by automation. An automated ball valve (or actuated ball valve) allows for remote operation, precise timing, and safety interlocking.

However, the valve is only as reliable as the “engine” driving it. Choosing the wrong actuator can lead to valves that fail to close under pressure or motors that burn out prematurely. In this guide, we’ll compare the two industry titans: Pneumatic and Electric actuators.

Table of Contents

Toggle1. Pneumatic Ball Valve Actuators: The Speed King

Pneumatic actuators use compressed air to rotate the valve. They are the most common choice in heavy industry.

The Advantage (Speed & Durability): They offer rapid opening and closing (under 1 second). Since they don’t use electricity to generate torque, they have a 100% duty cycle, meaning they can cycle thousands of times a day without overheating.

Fail-Safe Options: You can easily specify a “Spring Return” (Fail-Closed) model. If your plant loses power or air pressure, the mechanical spring automatically slams the valve shut—critical for emergency shutdowns.

Best For: High-cycle applications, hazardous environments (explosion-proof by nature), and systems where compressed air is already available.

2. Electric/Motorized Ball Valve Actuators: The Precision Specialist

Electric actuators use a motor and a gear train to turn the valve.

The Advantage (Control & Infrastructure): They are easier to install in remote locations where running air lines is impossible. They provide high torque in a compact package and offer excellent positioning control (e.g., stopping the valve at exactly 45 degrees).

The Limitation: They typically have a lower duty cycle (usually 25% to 50%). If the motor runs too frequently, it will overheat. They are also significantly slower than pneumatic versions (usually 10–30 seconds per cycle).

Best For: Water treatment plants, HVAC systems, and applications requiring precise flow modulation.

3. The “Torque Gap”: A Common Engineering Mistake

The biggest reason an actuated ball valve fails is an undersized actuator.

The “Safety Factor” Insight: A ball valve’s torque isn’t constant. It takes significantly more force to “break” the seal (Breakaway Torque) than it does to keep it moving.

Field Advice: Always apply a 25% to 30% safety factor to the valve’s published torque. If you are using a metal seated ball valve or handling viscous fluids like oil, increase that safety factor to 50%. An under-torqued actuator will eventually stall, leading to a “half-open” valve that can ruin your seats through erosion.

4. Pneumatic vs. Electric: Comparison Matrix

| Feature | Pneumatic Actuator | Electric Actuator |

| Cycle Speed | Fast (1-2 seconds) | Slow (10-60 seconds) |

| Duty Cycle | 100% (Continuous) | 25% – 50% (Intermittent) |

| Fail-Safe | Simple (Mechanical Spring) | Complex (Battery Backup/Supercapacitor) |

| Cost | Lower (per unit) | Higher (per unit) |

| Power Source | Compressed Air | Electricity (AC/DC) |

5. Mounting Standards: Look for ISO 5211

When you buy an automated ball valve package, ensure the valve has an ISO 5211 mounting pad. This is the international standard for the interface between the valve and the actuator.

Why it matters: Using a standardized pad means you can easily swap out a failed actuator or upgrade from manual to automated in the future without having to fabricate custom brackets.

Conclusion: Balancing Speed, Cost, and Control

If your priority is speed and safety in a harsh environment, go Pneumatic. If you need easy installation and precise control in a clean environment, go Electric. Whatever you choose, remember: the actuator is the brain of your valve—don’t cut corners on the torque.