In the world of industrial automation, three terms appear almost every day: control valves, regulating valves, and instrument valves. All three are called “valves,” all can open or block the flow of fluid, yet they play completely different roles in real engineering systems.

In short:

Control Valve → The actuator that executes control commands

Regulating Valve → The throttling core that shapes the flow characteristics

Instrument Valve → The “invisible infrastructure” that ensures accurate measurement

To understand how they differ, we must look at how each one fits into a real control loop and how industries use them under different priorities.

Table of Contents

Toggle1. A Simple Control Loop: Where Each Valve Really Belongs

Imagine a common task: maintaining stable pressure on a steam pipeline feeding downstream equipment.

A standard closed control loop includes three key parts:

Measurement

Pressure transmitter

Instrument valves (manifold, needle valve, mini ball valve, etc.)

Control

DCS/PLC issuing commands

Execution

Control valve

Inside the control valve, the regulating valve body is the throttling element

These three components form a logical chain:

Instrument valves → determine whether the numbers you “see” are accurate

Regulating valve → determines whether each small change in signal results in predictable flow changes

Control valve → determines whether the system can execute commands smoothly and reliably

Understand this loop, and you understand their true engineering positions.

2. How Different Industries View These Three Valves

The same three types of valves play entirely different roles depending on the industry:

Chemical & Fine Chemical

The focus is on control quality:

Overshoot

Settling time

Valve linearity

Deadband

Poor regulating valve characteristics can cause reactors to swing between overheating and overcooling.

Power Plants (especially supercritical/ultra-supercritical units)

What matters most is safety and reliability:

High-temperature, high-pressure steam

Anti-erosion, anti-cavitation

Long-term, jam-free operation

Here, control valves are essentially life-protection devices.

Natural Gas Transmission & City Gas

Emphasis is on:

Pressure regulation stability

Tight shutoff

A single pressure-regulating valve is responsible for city-level safety.

Water Treatment & Environmental Protection

Priorities shift toward:

Cost-effectiveness

Easy maintenance

Mediums are mild, but the valve quantity is high; lifecycle cost matters more than extreme performance.

Different industries amplify different “character traits” of the three valves.

3. Control Valves: The Dynamic Actuator of the Process

In an automation system, a control valve is not merely a valve. It is the final control element—a dynamic response device.

Its purpose is not simply to open or close; it responds to the controller’s commands and converts them into measurable physical changes.

Signal Flow in a Control Valve

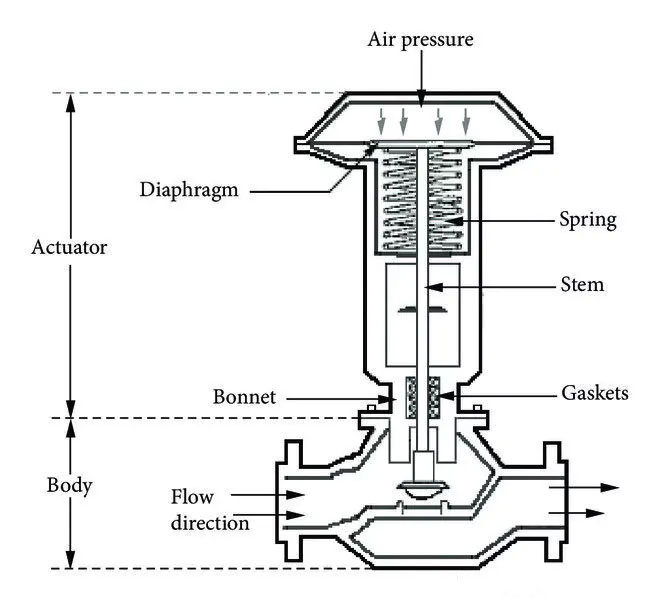

Controller output: 4–20 mA, pulse, or Fieldbus signals

Positioner: translates the signal into valve stem displacement

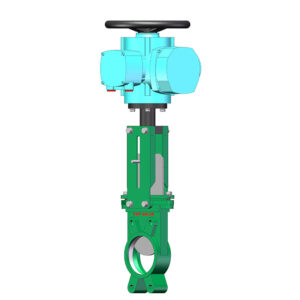

Actuator: pneumatic, electric, or electro-hydraulic; generates force or torque

Regulating valve body: performs the actual throttling

Thus, a control valve consists of:

Valve body (throttling)

Actuator (movement)

Positioner (signal correction & control)

It must solve three engineering challenges:

Process parameters continuously change → require real-time adjustment

Mechanical nonlinearity → needs linearization and compensation

Disturbances (pressure fluctuations, viscosity changes) → require stable response

A control valve is not a piece of hardware—it is a behavioral system.

Its quality is defined by whether it can execute commands reliably, not by material alone.

4. Regulating Valves: The Throttling Core of Process Control

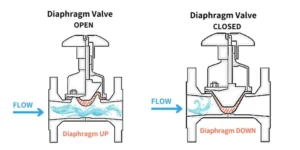

A regulating valve is often mistaken for a control valve, but it is more like the engine cylinder—its sole mission is throttling.

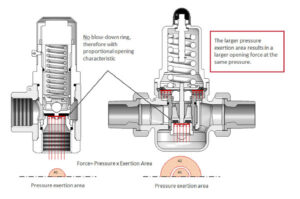

Throttling is the physical essence of all flow regulation:

change resistance → change flow → change process variables.

What a Regulating Valve Must Deliver

Predictable flow characteristics (e.g., equal percentage)

Stability under high differential pressure

Resistance to cavitation, flashing, and erosion

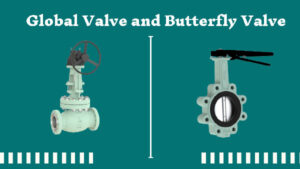

Different structures—single-seat, double-seat, cage-guided, eccentric rotary, V-ball—exist to handle different energy dissipation mechanisms.

Pressure Drop Handling

Single-step drop → prone to cavitation and noise

Multi-stage/multi-hole/cage/maze → reduces energy density and eliminates cavitation

Flow Characteristics

Linear – flow proportional to opening

Equal percentage – gentle at first, sensitive later; great for large ΔP systems

Quick opening – suitable for on/off behavior

The regulating valve determines whether the process is controllable.

The control valve determines whether the system can execute the control.

One is physics; the other is system engineering.

5. Instrument Valves: The Hidden Infrastructure Behind Accurate Measurement

Instrument valves are often underestimated. They are not flashy and have no dynamic movement, but they determine the accuracy of every measurement.

Pressure transmitters, differential pressure transmitters, level instruments—all rely on proper:

isolation

venting/draining

impulse line integrity

The True Value of Instrument Valves: Avoiding Interference

They provide four hidden yet critical functions:

Isolation – protects sensors from sudden pressure shocks

Stabilization – dampens pulsations via impulse tubing

Venting/draining – prevents air locks and liquid traps

Calibration & switching – allows maintenance without process shutdown

A simple 3-valve or 5-valve manifold handles:

Process isolation

Venting/draining

Calibration and transmitter replacement

If instrument valves are selected or installed incorrectly, the entire system becomes blind—no matter how good the control or regulating valves are.

6. Selection Perspectives

Control Valve Selection

Focus on:

Is the application modulating, shutoff, or emergency isolation?

Required response speed & closing pressure

Reliability, fail-open/fail-close position

Signal modes (NO/NC, fail-safe position)

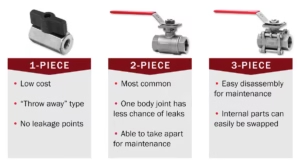

Regulating Valve Selection

Focus on:

Medium properties (corrosive? crystallizing? solids?)

Pressure drop and potential cavitation

Required flow characteristic (linear vs equal percentage)

Instrument Valve Selection

Focus on:

Pressure/temperature rating

Connection type (threaded, welded, compression fitting)

Required isolation level (double block and bleed?)

Space for maintenance

Sampling requirements

You are not selecting a “valve”—you are selecting a system behavior.

7. Typical Failures and Diagnostic Logic

Control Valve Issues

Slow response

Stiction

Hunting

Travel deviation

Causes often lie in positioner tuning, air supply, actuator friction, or spring preload.

Regulating Valve Issues

Noise

Cavitation

Trim erosion

Internal leakage

Stem sticking

These indicate early selection mismatches or improper throttling design.

Instrument Valve Issues

Micro-leakage

Blockage

Incomplete venting → measurement drift

Many “sensor faults” originate in the impulse line or manifold, not the transmitter.

A good diagnostic order is:

Measurement → Instrument valves → Regulating valve → Actuator → Controller

Most problems are not caused by PID.

8. Safety and Interlocks

Control Valves

Used in:

ESD systems

Combustion protection

Interlock shutdown

Critical requirements:

closes fast, closes tight, closes reliably.

Regulating Valves

In hazardous media:

Leakage class

Stem sealing (bellows seal, packing type)

These directly affect personnel and environmental safety.

Instrument Valves

A key part of isolation and bleed systems, ensuring the pressure is truly released before maintenance.

In a SIL (Safety Integrity Level) assessment, all three types form part of the SIF (Safety Instrumented Function) chain.

They are not separate components—they are one interconnected safety ecosystem.

9. Conclusion

To summarize in precise engineering language:

Control valve → governs dynamic response; it is the execution device

Regulating valve → governs energy dissipation and throttling; it is the process core

Instrument valve → governs signal quality; it is measurement infrastructure

Together they determine:

whether a system can be controlled

whether it can be controlled stably

whether it can be measured accurately

This is the fundamental logic of industrial control:

Measurement → Throttling → Execution.