When an essential gate valve in your facility fails—whether it is a stuck gate valve or a leaking stem—the decision to repair or replace depends on a thorough internal inspection. For heavy-duty industrial valves, a “rebuild” can often extend the service life of the asset, provided the valve body remains structurally sound.

This guide provides a professional walkthrough for gate valve disassembly, inspection, and repair protocols.

Table of Contents

Toggle1. Safety First: Pre-Disassembly Protocol

Before attempting any gate valve repair, you must ensure the safety of the maintenance team and the integrity of the surrounding system:

Depressurization: Verify that the line is completely depressurized. Even a small amount of residual pressure can turn a loose bolt into a dangerous projectile.

Drainage: Ensure the medium (especially if corrosive or high-temperature) has been fully drained.

LOTO (Lockout/Tagout): Follow OSHA standards to lock out upstream and downstream isolation valves to prevent accidental inflow.

2. Gate Valve Disassembly: The Step-by-Step Process

To take apart a gate valve correctly, follow this sequence to avoid damaging the machined surfaces:

Step 1: Remove the Actuator/Handwheel

Loosen the handwheel nut and remove the handwheel. For automated systems, disconnect the pneumatic or electric actuator, ensuring all power sources are isolated.

Step 2: Disassemble the Packing Gland

Loosen the gland bolts and remove the packing flange. This exposes the valve packing, which is the primary seal for the stem.

Step 3: Remove the Bonnet (Valve Cover)

Unscrew the bonnet-to-body bolts. For larger valves, you may need a hoist. Carefully lift the bonnet vertically. In many designs, the gate (wedge) will lift out along with the stem and bonnet.

Step 4: Extract the Stem and Gate

Rotate the stem to unscrew it from the gate (for rising stem valves) or slide the gate off the stem T-slot.

3. Critical Inspection Points: Repair or Scrap?

Once the gate valve disassembly is complete, inspect these three areas to determine if a gate valve rebuild is viable:

The Stem Threads: Look for “galling” or flattened threads. If the valve stem keeps spinning, it is usually because these threads have been stripped due to forcing a seized valve.

The Seating Surfaces: Check the gate and the body seats for “wire-drawing” (grooves cut by high-velocity leaks) or deep pitting. Minor scratches can be lapped, but deep gouges often mean the valve is beyond repair.

The Body Cavity: In slurry or ash service, check for “bottom-out” erosion. If the bottom pocket is filled with hardened scale, it prevents the gate from closing fully.

4. Rebuilding the Valve: Key Steps

If the components are salvageable, proceed with the rebuild:

Cleaning: Use a wire brush or specialized solvent to remove all mineral scale and rust from the internal cavity.

Lapping: Apply lapping compound to the gate and seats to ensure a perfectly flat, metal-to-metal seal.

Replacing Soft Goods: Always replace the stem packing and the bonnet gasket. Reusing old packing is the most common cause of post-repair leaks.

Reassembly: Lubricate the stem threads with high-temperature anti-seize compound before reinserting.

5. When Maintenance Isn’t Enough: The Case for Ceramic

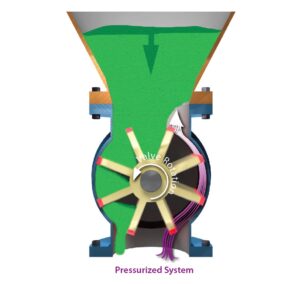

In many industrial plants—especially those handling coal ash, mining slurry, or cement—standard metal gate valves are a poor investment. If you find yourself performing a gate valve repair every few months, the medium is likely too abrasive for metal-to-metal contact.

Why upgrade to a Ceramic Knife Gate Valve?

Zero Pocket Accumulation: Knife gate designs eliminate the bottom pocket where ash gets stuck.

Erosion Resistance: While metal seats pit and groove, structural ceramics remain untouched by high-velocity particles.

Cost Efficiency: A ceramic valve may cost more upfront, but its service life is often 10x longer, eliminating the labor and downtime costs of repeated rebuilds.

Conclusion

Knowing how to repair a gate valve is an essential skill for any maintenance engineer. However, the mark of a great engineer is knowing when to stop repairing a failing design and when to upgrade to a superior solution.