Wastewater treatment is a brutal environment for flow control. Between abrasive grit, stringy fibrous sludge, and corrosive chemical additives, a standard valve is often doomed to fail. The most common headache for plant operators is valve clogging—where solids build up in the valve cavity, preventing a full shutoff or causing the actuator to burn out.

If you are tired of constant maintenance shutdowns to clear blocked lines, you don’t need “stronger” valves; you need smarter valve geometry. Here is how to select the right valves to handle the toughest sludge problems.

Table of Contents

Toggle1. The Knife Gate Valve: The Sludge Specialist

For lines carrying thick sludge or suspended solids, the Knife Gate Valve is the undisputed champion.

How it solves the problem: Unlike a standard gate valve with a bottom groove (which fills with sand and prevents closing), a knife gate has a sharpened stainless steel blade.

The Action: The blade cuts through thick slurries and severs fibers as it closes.

Design Tip: Look for Perimeter Seating or O-port designs that push solids out of the sealing path rather than trapping them.

2. Plug Valves: Handling Abrasive Grit

In the “Grit Chamber” or primary sludge lines, sand and small stones act like sandpaper on valve internals.

Why it works: Eccentric Plug Valves are the industry standard here. The plug only contacts the seat at the very last moment of closure.

The Benefit: This minimizes friction and wear. Additionally, the flow path is straight and unobstructed, meaning there are no pockets for “dead” sludge to accumulate and rot.

3. Pinch Valves: The “No-Clog” Ultimate Solution

When dealing with extremely thick, raw sludge or lime milk (used for pH adjustment), even a knife gate might struggle.

The Mechanism: A Pinch Valve uses a flexible rubber sleeve. To close the valve, a mechanism simply pinches the sleeve shut.

The Benefit: There are zero internal metal parts in contact with the media. It is a full-bore design, so when open, the valve is essentially just a piece of pipe. It cannot clog because there are no “nooks or crannies” for solids to hide.

4. Check Valves in Wastewater: Avoiding “Roping”

Standard swing check valves often fail in wastewater because hair and fibers wrap around the hinge pin—a phenomenon known as “Roping.”

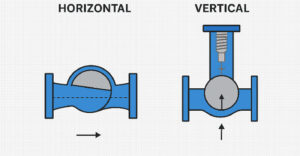

The Solution: Use Ball Check Valves. A rubber-coated ball is pushed into a side pocket by the flow and falls back onto the seat when the flow stops.

The Benefit: The ball rotates constantly, making it “self-cleaning” and virtually impossible for fibers to catch and cause a blockage.

5. Material Selection: Fighting the “Hidden” Corrosion

Wastewater isn’t just dirty; it’s chemically aggressive.

H2S Gas: Causes “Sulfide Stress Cracking.”

Ferric Chloride: Used in phosphorus removal, it eats through standard carbon steel.

The Strategy: Use 316 Stainless Steel for internals and ensure all ductile iron bodies are coated with fusion-bonded epoxy (FBE) to prevent external and internal rust.

6. Wastewater Valve Selection Guide

| Application | Recommended Valve | Why? |

| Raw Sewage / Sludge | Knife Gate Valve | Cuts through fibers/solids. |

| Grit & Abrasive Media | Eccentric Plug Valve | Resistant to wear and erosion. |

| Chemical Dosing (Lime) | Pinch Valve | 100% clog-free; isolated media. |

| Pump Discharge | Ball Check Valve | Self-cleaning; no “roping” risk. |

Conclusion: Reliability Starts with Geometry

In wastewater, a valve fails because its design allows solids to settle. By choosing valves with self-cleaning actions and unobstructed flow paths, you can reduce your maintenance man-hours by up to 70%. At our facility, we specialize in high-durability wastewater solutions designed to keep the sludge moving.