In the world of fluid control, chloride ions (Cl-) are known as “hidden killers.” Their small ionic radius and high permeability allow them to penetrate the passive film of metals, leading to Pitting, Crevice Corrosion, and Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC).

For engineering teams, selecting valves for chloride service involves a difficult “Trilemma”—balancing performance, cost, and long-term stability.

Table of Contents

ToggleTrilemma 1: Corrosion Resistance vs. Procurement Cost

The most intuitive defense against chloride is using high-performance alloys like Titanium, Hastelloy, or Monel.

The High-End Choice: These alloys form a dense, stable passive film. In a desalination project’s Reverse Osmosis (RO) system, Titanium valves can operate in seawater (15,000 mg/L Cl-) for over five years without a single leak.

The Budget Trap: Standard SS304 or SS316L are cost-effective but risky. While 316L is superior to 304, it often fails in concentrations exceeding 500mg/LCl-.

Strategic Insight: Using a “cheap” 316L valve in a 800mg/L brine line may save 80% on initial costs, but a failure within 8 months leads to downtime losses that far exceed the price of a Titanium valve.

Trilemma 2: Material Performance vs. Manufacturing Workability

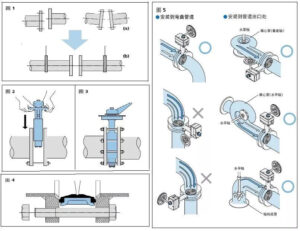

When alloys are too expensive, Lined Valves (PTFE/PFA/Rubber) are a popular alternative. They isolate the metal body from the corrosive medium entirely.

The Processing Gap: Unlike metals, liners are difficult to process. If the sintering temperature is off by just a few degrees, microscopic bubbles form. Chloride ions permeate these bubbles, causing the liner to bulge and fail.

The Machining Hurdle: High-performance alloys (like Hastelloy) are notoriously difficult to machine. Their hardness wears down tools 3–5 times faster than standard stainless steel, and welding requires extreme expertise to prevent Intergranular Corrosion.

Trilemma 3: Current Conditions vs. Future Stability

Industrial environments are rarely static. Chloride concentrations, temperatures, and pressures fluctuate with process adjustments.

The Risk of “Just Enough”: A coal chemical plant may select 316L based on an initial 300 ppm chloride count. If the concentration cycles up to 800 ppm due to water recycling, the valves will suffer Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) within two years.

The Risk of Over-Engineering: Conversely, installing a Hastelloy valve for a stable 100 ppm environment is a waste of capital.

The Solution: A Science-Based Selection Matrix

To break the Trilemma, we use the PREN (Pitting Resistance Equivalent Number) to categorize risks.

| Chloride Risk | Concentration | Recommended Material | PREN Range |

| Low | < 200 ppm | SS316L | 23–26 |

| Medium | 200 – 2,000 ppm | Duplex 2205 / 904L | 30–36 |

| High | > 10,000 ppm | Super Duplex 2507 / Titanium | 40+ |

Conclusion: Beyond Initial Price

Cracking the chloride code is not about picking the most expensive metal; it is about Life Cycle Cost (LCC). By matching the PREN value to your specific chloride concentration and accounting for temperature fluctuations, you can find the “Sweet Spot” between performance and budget.

At tot valve, we provide comprehensive metallurgy consultations to ensure your valves are built for the reality of your environment, not just the data on a spec sheet.